The Case of the Disappearing Networks

“A composition first has to be written, then it has to be published in order to be circulated, at least after ca.1780. It has to reach public consciousness by a first performance and then remain there through some regularity of performance. This is less likely to happen without some critical attention in print and a positive assessment at least sometime near the work’s debut. Although these steps seem the most basic stages on the road to permanency and potential canonization, they actually take place well into the process.”

We are all aware of the Bechdel test – the requirement for a film to have two named women have a conversation on a topic other than a man. We are also well aware of how badly the film industry still fares under the application of this test. Disney is particularly culpable on this – heaven forbid any woman should exist for a reason beyond the male sphere.

I am now applying the Bechdel test to the stories of women in music, with depressingly familiar results. I have written this month in some detail about composer Rosalind Ellicott and her relationship in particular with the Three Choirs Festival. She started by singing with them, moving quite swiftly to being a regular on their roster of contemporary composers. Several of her cantatas earned their fame here, though she doesn’t make the abbreviated list on the festival’s own website (Ethel Smyth is the only historical woman here):

“The festival has always prided itself on bringing new works to its audiences, and over its 300-year history has included premieres by Edward Elgar, Arthur Sullivan, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Hubert Parry, Ethel Smyth, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Frederick Delius, Camille Saint-Saëns, Judith Weir, Judith Bingham, James MacMillan and Cheryl Frances Hoad, many of which were conducted by the composers themselves. Numerous celebrated composers, conductors and soloists have been welcomed to the festival [...]”

There has been considerable speculation in the admittedly small literature on Ellicott as to how she succeeded in attaining this relationship. Let’s leave aside the fact that this is under the microscope at all, and look at this assertion, put plainest on Wikipedia: “It has been suggested that her father's position as a bishop enabled her to have some of her works performed at the Three Choirs Festival.”

Why do I take issue with this? It’s because not only is there the obvious assumption that Ellicott could not possibly have accrued a commission by her own merit, but that it must be a male figure in her life that facilitated her career. Why must it be the father, whose interest in music was small, and not the mother, a singer who sat on several committees and was known for a considerable number of her own public performances? To call her mother an amateur singer is to underestimate her sphere of influence, which included the festival. Another route in may have been via Hilda Wilson, the well-known and successful singer who was a fellow student of Ellicott’s, and taught her singing; in the younger musician’s words, “She instructed me in the best way of producing my voice. I should like to say that I owe more to her than I can ever repay.” Wilson often sang with the Festival in the 1880s and -90s. Surely it is just as likely, if not more, that these female networks were the ones that enabled Ellicott’s inclusion?

Alice Verne-Bredt, who came more to my current attention via the album of trios I reviewed last week, is another case in point of a member of a professionally important female network. She belonged to a German family that emigrated to the UK in the 1850s, anglicizing their name in the process. The sisters, however, each chose a different version. Alice double-barrelled her name with her husband’s, Adela and Mathilde remained known as Verne, and Mary, who spent much of her performing life in German-speaking countries, reverted to the original Wurm, although without the umlaut. The sisters performed each other’s works, as well as giving concerts together in their respective countries of residence. Wurm was a conductor as well as a pianist, thus giving a useful – and rarer – opportunity to have larger works heard.

Of course, there are many more of these – I am always particularly taken with the connections between the women at the Academy in the 1830s, singers, pianists, composers, and how they supported each other in both public and private spheres. Both peer and intergenerational support is evident in the stories and concert reviews that start appearing from the next decades. Indeed, Ellicott herself in turn does her part for the next generation of Academy students.

The Bechdel test perhaps isn’t quite the analysis to be applied here, but there is certainly the feeling that if a man doesn’t play a defining role in a woman’s career, we’d better shoehorn one in somehow. This has far greater ramifications than just to rewrite women and their creative authority – it also demonstrates what little impact we afford teaching, family, student community, and all the other networks that arise from the business of simply living.

The Dappled Life of Agnes Zimmermann

This week’s offering is the third in an Agnes Zimmermann triptych. After a biography (rectifying some incorrect information elsewhere on the internet), and a reflection on a 2020 recording of her three violin sonatas, today’s blog post is about the ways in which her life as a 19th-century female musician still resonates today, with me, a 21st-century female musician.

Zimmermann has walked with me for the past few weeks. I find this with the women I research, that they become companions in more than performance or writing. Evangeline Livens did for a while, followed by Clara Macirone. Now, I find myself drawing on Zimmermann when talking about musical space, about chamber music, about manuscripts. I co-adjudicated the Historical Women Composers Prize at the Academy last week, alongside Diana Ambache. It is a requirement that every entry for this prize is chamber music, so we had from duos to quintets. Zimmermann was a consummate chamber musician, so this was right up her alley - and I found that I share her passion for space and light in the texture of a collaborative performance. It was an image of her manuscript that I had in my head for this realisation, that perfectly structured writing that allows light between the notes of even the thickest textures. It isn’t necessarily about literal silence, although breath is of course essential, but about the play of transparency through to opaqueness in the performance as well as in the writing. This, Zimmermann has made explicit for me some of the musical priorities I hold, but that I had not put words to.

The other way in which Zimmermann feels very present to me currently is in her life as she lived it. I wrote last week about imagining the composer in the act of writing, but this goes even further, in part fueled by this:

There’s a lot written on mental load, and second (third/fourth) shifts, but it’s not quite these areas that strike a chord for me when I think of women composers of the past. Classical composition – or, to be frank, life as any kind of classical musician – has never been kind to other obligations, not least in how it is written about. The idea of the composer renouncing all else for his (pronoun chosen carefully) art is so entrenched, so removed from everyday life, that the woman who manages to find a few minutes to write a song in between loads of laundry and feeding the children, must necessarily have less of the sublime in her writing. I see that race not just as running towards the goal of a complete artwork, but also running towards the goal of recognition.

Many of Zimmermann’s works were written in the years immediately after her time at the Academy. This is very common, not just for women composers, and I wonder how much it is because of the support and recognition that comes with a successful studentship, which tends to start to fall away as new students take their place. And for composers who do not have recourse to other systems, this can prove fatal to a career. Zimmermann was luckier than many women, as her performing life kept her in the public eye, but what happens to women for whom the printed page is their main way of disseminating creativity?

From 1890-1908, Zimmermann did take a step back from public music. This was during her time living with Lady Louisa Goldsmid, activist for education, both for women and for children. In Queer Episodes in Music and Modern Identity, Sophie Fuller wrote of this relationship, of which little is known, causing Fuller to reflect:

“However I, living and working in a different century, decide to name Agnes Zimmermann and Louisa Goldsmid’s relationship, the facts of the devotion, the interrupted career, and the shared home remain a powerful reminder that women’s varied relationships with each other have always played a vital, if often neglected, role in their histories. Despite what can seem like overwhelming attempts to show otherwise, not all women can be defined by their relationships with men and male institutions […].”

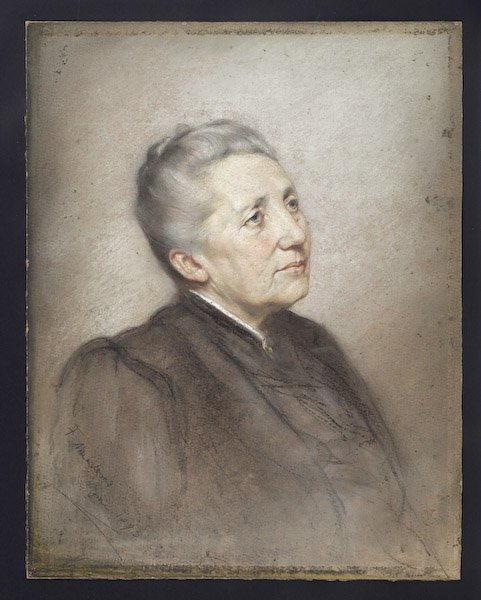

In the eighteen years that the two women lived together, Zimmermann performed little and published nothing. This was not due to domestic necessity; Lady Goldsmid’s will leaves money to many loyal servants, including a butler, housekeeper, cook, coachman, and several housemaids. It is a reminder, though, that creativity has often been enabled by women; and Fuller’s question of what women-living-with-women does to their “artistry and creativity” is a far-reaching one. From Zimmermann and Goldsmid, to Macirone and her sister, or Dolby and her mother, or Mathilde Kralik and Alice Scarlat, and even to the servants that tended them and their houses, women pave the way for recognition, not just of creative genius, but of the manifold threads that make up creative work. Several months ago I mentioned the mothers who start their talented daughters on their instruments; the idea of a muse, “A person or personified force who is the source of inspiration for a creative artist,” suddenly becomes one of great power and agency. What caused Zimmermann to write certain works? To play them?

Zimmermann remains a role model for me, and a source-to-come of rich possibility. In the meantime, I finish with a quote from philosopher Gilles Deleuze, of which Sophie Fuller’s reflections on Zimmermann remind me:

“Difference is not a negation of sameness. Difference may have a meaning that is independent of sameness, and repetition may be independent of the sameness of any given events or actions.”

19C RAM Singers on Stage and Platform

In looking through playbills and reviews of the UK musical scene in the mid- to late nineteenth century, it always amazes me just how often names connected with RAM crop up. Of course, given that the Academy was until 1882 the only college in the country turning out professional performers, it’s not entirely to be wondered at; but this is also testament not just to the performers themselves, but to the extraordinary teachers that the institution managed to procure throughout even the first decades of its existence.

I’ve written before about just how many women at this time were able to earn a living through music, most through piano and/or singing (organ came only slightly later). From mid-century, being a former student of the Academy certainly became a selling point in the many advertisements for teaching services. There was often mention in these of specific teachers as well, demonstrating just how much these musicians were household names.

Many women also became performers, both nationally and internationally. One of the first, in just the second intake of students, was Fanny Dickens (1810-1848), whose career was cut short by her early death from tuberculosis at the age of 38. She had been known throughout the UK especially for the concerts she gave with her husband Henry Burnett, also a singer. (It might be added here that it can be quite difficult to unearth anything about Fanny – a search of archives tends to produce results pertaining to her younger brother, who wrote some books.) Two years after the beginning of Dickens’s studentship came Anna Bishop, who has already featured on this website. She was one of the most-travelled singers of the nineteenth century, sallying forth on horse cart, train, ship, or whatever mode of transport would get her to where she was going, on any continent or island. But more importantly, she was clearly a singer of wide-ranging talents, with a repertoire that encompassed opera and concert works from Balfe and Bishop (her first husband) to Handel, Mozart and Beethoven, to Italian composers such as Donizetti and Bellini. Bishop was contemporaneous with the rather less flamboyant but equally successful Mary Shaw (1814-1876), contralto advocate of both Rossini and the modern composer Giuseppe Verdi. She was another singer who benefitted from Mendelssohn’s enthusiasm for British singers, appearing at the Leipzig Gewandhaus several times.

The 1830s began with the admission of such figures as Charlotte Birch (c1815-1901). Active particularly on the oratorio circuit, she entered seven years before her younger sister Eliza Ann (1825-1862), for whom she was the recommender. Charlotte was more in demand than her entry in the 1900 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians intimated:

“Miss Birch possessed a beautiful soprano voice, rich, clear, and mellow, and was a good musician, but her extremely cold and inanimate manner and want of dramatic feeling greatly marred the effect of her singing.”

Sadly, her career was cut short by encroaching deafness, though she remained living with her sister, as so many women of this time did, teaching singing from their residence in Baker Street. Eliza roamed further afield, travelling to other cities to give occasional classes and masterclasses.

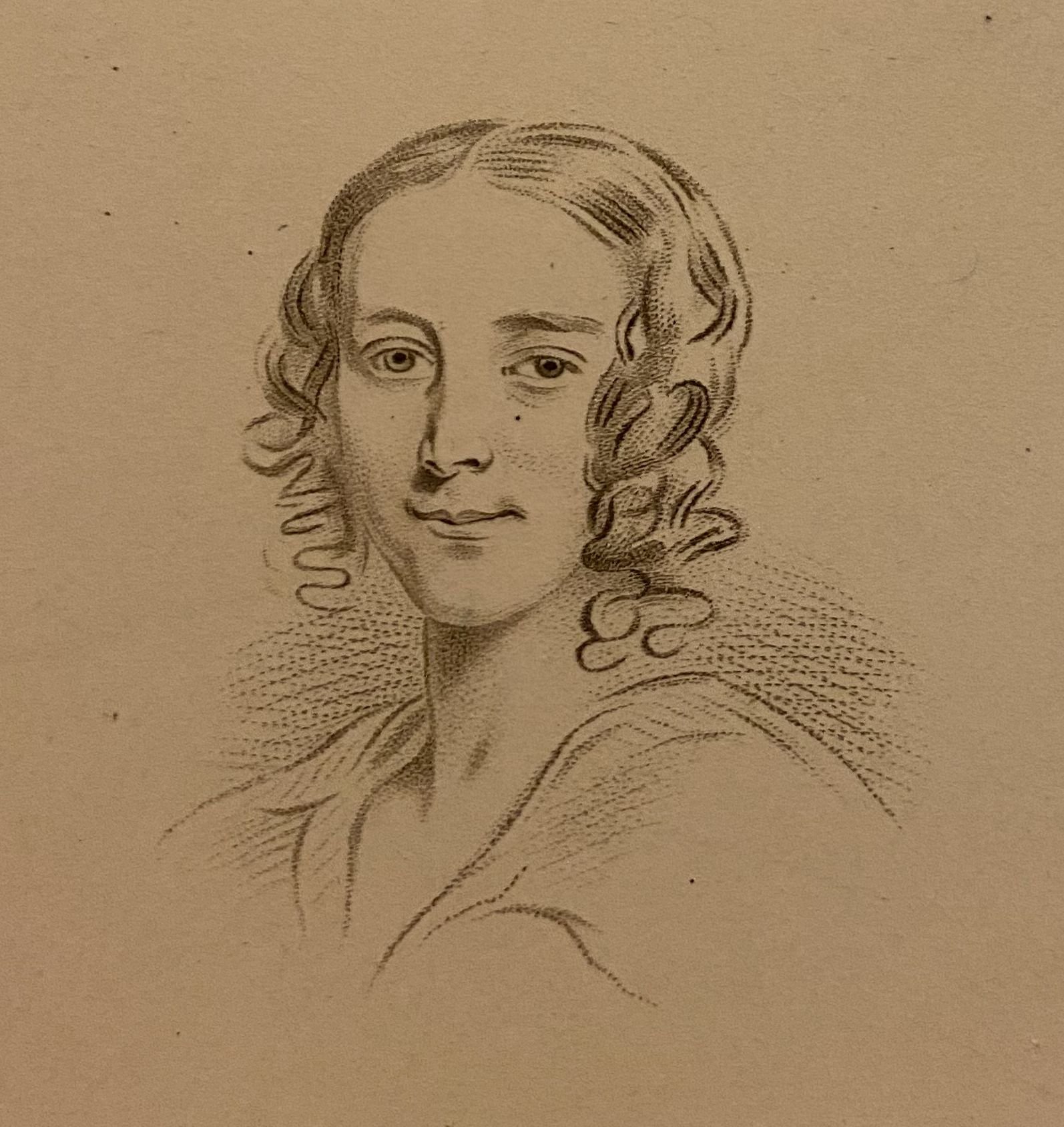

Charlotte Dolby 1821-1885 was another famous figure well into the later century, and has also been a highlight of these pages, over on Composer of the Month. Like many of the singers mentioned above, her singing career gave way to other enterprises in later life, though her name remained a drawcard for her pupils.

By the 1860s, female students far outnumbered male, and the proliferation of successful musicians amongst their numbers continued apace. Singers such as Edith Wynne,

Mary Davies, Rebecca Jewell and Arabella Smyth, to name but a few, made their name both within the walls of the Academy and on concert platforms throughout the country. Next month we will look at the change in instrument availability that resulted in a much broader impact for women in the profession.

Oboe and trumpet, anyone?…

How we listen: Contemporary v 19C audiences, with a stop in between

Myra Hess plays in a National Gallery concert during WWII

Concert Etiquette. Hands up who “gets” it?... Hands up who just gets confused?... Oh, just me then.

Seriously though, there’s a whole thing around how to behave in concerts that I have never quite got my head around, mainly because I’m terrible at sitting still. I had a conversation with a pianist once, who had just done a recital in the Wigmore Hall. He complained about the audience member in the front row who appeared to read a book the whole way through the event. If she was going to pay so little attention, he grumbled, couldn’t she just have stayed home?

Now, while sitting in the front row to read your book is perhaps a whole issue in itself, I can well imagine that she might possibly be the kind of listener who actually pays more attention, not less, through the lens of her book. While I might not want to read in a concert, I would have to confess to being an inveterate doodler/drawer/crocheter. If my hands are engaged, so is my mind and so are my ears. The way concert etiquette works, though, I only do this if I can do so undetected. I am well aware that this is seen as impolite to both performers (you’re not paying enough of the right kind of attention) and other members of the audience (you’re being distracting). Thanks, Hanslick. Maybe we should start splitting concert halls like weddings: “Good evening, madam, which side would you like? The sitting still side, or the doodlers? Right this way, follow me.”

Having said all that, it has been more and more in my consciousness just what it means for composer, performers and listeners that ways of listening have changed so much, even for the most traditionalist of concertgoers, and just how much, therefore, we ask of audiences. Even one hundred years ago, the only way of hearing music for most people – at least, music played by others – was to hear it live and in its entirety. Filing into a hall where people sat in serried rows and just listened was par for the course, if you liked that sort of thing. People were accustomed to it. (I differentiate between this and listening to oneself play partly because I find musicians some of the worst at sitting still in concerts.)

Things changed slowly but surely as technology made music ever more present, until we arrive at our current culture, with its almost incessant soundtrack. It’s made an enormous difference to how we engage with music, and it has dawned on me just how much of an ask it is to expect listeners to fulfil the role of a pre-recording audience, to leave their 21st-century ears and thought processes at the door. For some, this is second nature. For others, it is a struggle that can’t be won, no matter their relationship with the music itself. I mentioned Eduard Hanslick above, that proponent of “active” listening over “passive” listening, who did little to disguise his contempt for people who might simply let music wash over them in a wave of sensory enjoyment. He would have hated lift music.

E. M Forster wrote beautifully of what an audience really is, as opposed to what it’s assumed to be. He has just been to one Myra Hess’s National Gallery concerts that happened almost weekly throughout WWII:

“There is no such person as the average concert-goer, and no one can speak in his name. Not only does our enjoyment of music differ, but our attention wanders from it in different directions, and returns to it at different angles; so that if the soul of an audience could be photographed it would resemble a flight of scattering dipping birds, who belong neither to the air nor the water nor the earth. In theory the audience is a solid slab, provided with a single pair of enormous ears, which listen, and with a pair of hands, which clap. Actually it is that elusive scattering flight of winged creatures, darting around, and spending much of its time where it shouldn’t, thinking now “how lovely!”, now “my foot’s gone to sleep”, and passing in the beat of a bar from “there’s Beethoven back in C Minor again!” to “did I turn the gas off?” or “I do think he might have shaved”. Meanwhile Beethoven persists, Beethoven does not flicker, Beethoven plays himself through. Applause. The piano is closed, the instruments re-enter their cases, the audience disperses more widely, the concert is over.”

Christiane Tewinkel has also written about internal distraction being far more important in analysing a listening experience than is external distraction (“Everybody in the Concert Hall should be Devoted Entirely to the Music”: On the Actuality of Not Listening to Music in Symphonic Concerts”, from The Oxford Handbook of Music Listening in the 19th and 20th Centuries) ; but alongside this, we need to think about the choices we make that were once deliberate and now so engrained in our everyday life that we have forgotten that they were once voluntary. Interestingly, in some of these choices we seem to have returned to nineteenth-century values. The hierarchy of genre is re-dissolving. Just as in the late nineteenth-century you could hear ballad and art song on the same platform at the same time, or explicitly programmatic music alongside the austerely formal, so now can you choose “programming” options that never would have made it onto many concert platforms of the late twentieth century. I remember one particular concert I gave with a flautist in the late 1990s, when the venue director only very reluctantly allowed us to play Schubert’s Trockne Blumen variations alongside Poulenc’s sonata (“After all, it’s not exactly great music, is it?”). Nowadays, I might even blow his mind further by playing one or two variations, perhaps separated by other works, as most of us might often choose to listen. The hegemony of the full work, a much later aesthetic conceit than is often thought, is vanishing rapidly. A nineteenth-century listener wouldn’t blink twice, being already accustomed to performer selection.

There are, though, many ways in which we have arrived at the opposite side to the pre-recording audience. I have already written of the fact that many people hear most of their music through head/earphones, and certainly the vast majority through technology. Those headphones ensure that even when we are in a room with others, our listening experience takes place in isolation. This isn’t just a psychological separation, but is also a technological one. My headphones and my device render a sound-world quite apart from yours, much more than is engendered by our different seats in a concert hall. Not only that, but the performers have vanished, too, disembodied and distant, although conversely, the sound they produce is closer than it’s ever been, pulsing straight into our covered ears. There is little pre-listening information readily available, bar the thumbnail of the often random artwork of the album cover; sometimes it’s hard even to find the name of either performer or composer, depending on the scrolling banner that a streaming service has decided fits their algorithms best. A case in point was the Dora Bright piano concerto recording that was reviewed on these pages last month. On one particular streaming service, the only search that brought up the recording was one for the [male] conductor. Composer and performer names drew a blank. The idea that liner notes might be hanging around somewhere is laughably archaic. You can often google these, but who has the time to do that very often? Our control over the time-lapse of music is completely different, too. We can choose to play a track over and over, or even start and stop within a track, skipping backwards and forwards over the phrases. We’ve become bookshop browsers, flicking through a paperback to see if we feel like committing to the longer read.

And what effect does all this have on how we approach concert-giving? Perhaps none; but it’s certainly worth being aware of the far wider range of listening habits to which we have to relate as performers. Personally, I enjoy fragmentation as well as the narrative arcs of full works. The range of choice, and the relationship between vastly different works, become programming tools that excite me. And as we return to live music making, the opportunities we have are endless. Here’s to a new era.

Women at the Academy in the mid-nineteenth century

While the first intake of female students to the Academy have disappeared into the mists of time, in the second intake, names that make it into public consciousness begin to appear. Fanny Dickens (1810-1848) is an example, entering the Academy in 1823. She studied both singing and piano, as most of the early students did, although it was singing that formed the basis of her career, piano being the side dish. She would go on to share platforms with other musicians such as her husband, Henry Burnett, German soprano Anna Schröder-Devrient, and French singer Rosalbina Caradori-Allan – until, of course, marriage and motherhood sharply curtailed her performing activities, and tuberculosis took her at the tragically early age of 38.

Another extremely famous figure was soprano Anna Bishop (1810-1884), who appeared in these pages last week. She studied at the Academy a few years after Dickens, starting on piano with Ignaz Moscheles before her extraordinary soprano voice was discovered, leading to her switch in focus. It is impossible to do justice here to Bishop’s colourful life; I am an enormous admirer of her talent, dedication and capacity for sheer hard work, and she will appear in these pages yet again later in the year. Her pianism, one infers, was not of the highest order, and thus she missed out on any of the early scholarships, such as the King’s Scholarships instated in 1834. The first two female students to win this, their musicianship now lost to the mists of time, were Catherine Halls and Louisa Hopkins. (Poor Catherine had to suffer from an inept press, who mixed up her last name with that of George Hall, one of the two male winners.)

By the next decade, female singers who had studied at the Academy were becoming well-known on the stages of the country and the world, such as Mary Shaw (1814-1876), Charlotte Sainton-Dolby (1821-1885), and Georgiana Poulter (dates unknown). Next to become known were the pianists, including the “child prodigy” Elizabeth Jonas (c1825-1877) who was “patronized by Her Royal Highness the Princess Augusta” and admitted to the Academy at the age of eleven in 1836 to study with Ignaz Moscheles and Thomas Attwood. Kate Loder (1825-1904) and Augusta Amherst Austen (1827-1877) were amongst these numbers; both also were organists who held positions in London churches. We also see the beginning of female students at the Academy who wanted to be known first as composers, rather than seeing this as an extra string to their bow. Clara Macirone (1821-1914) was one such musician. Her prolific letters to family members demonstrate that her performances were much more vehicles for her own music than they were pianistic displays. Another was Julia Woolf (1831-1893), composer of song and piano pieces, as well as an operetta, Carina, which by 1888 was “working itself into a genuine success at the Opèra Comique by reason of tuneful, if not very original, music, and chiefly and foremost by Mlle. Camille D’Arville’s artistc and fascinating singing and acting in the principal rôle,” as a contemporary review described.

Many of these women were able to sustain a good musical career, something we forget in our haste to draw them from shadows that are not as long as we might think. Those shadows do exist – Luise le Beau wrote in her autobiography of the extra-hard work that women had to take on, still to be ignored in the higher echelons of music culture. But they are not quite the shape we imagine, and they are not as all-encompassing as is often assumed, especially if we are willing to forego a cultural hierarchy that places public venues and public critical judgement at the top. Contrary to what it may seem, this can render these women even more invisible to succeeding generations – we still have a tendency for our eyes to slide over names that appear in programmes, as being available and thus not needing our help. But as any current composer will tell you, it’s the second performance that’s the hardest to procure. And why is one performance ever enough, when we are up against works with vast reception histories, of performances that occupy an entire spectrum of expertise, thus offering a rich, multi-faceted interpretation?

Of course, the style of music that many of these composers engaged with is often now seen as anachronistic. We have a deep suspicion of Victoriana, as I have already highlighted in the review of Dora Bright’s much later concerto. The complex nature of the friction between the death of Romanticism and the influence of the ‘long’ nineteenth century, coupled with a dawning discomfiture around the physical aspect of musicmaking in classical traditions, makes us wary of the unfettered sentimentality of some of this music. Indeed, sentimentality has come to be a pejorative term, not to mention at times aligned with contempt for the feminine, seen as sitting firmly in the same aesthetic. It’s a good way of dismissing all those nineteenth-century women who wrote songs to words that make us uncomfortable now. They must be “bad” composers, because the feeling they (deliberately) engender in the listener seems no longer viable.

Here’s a performance of one of Kate Loder’s piano works, Voyage Joyeux.